How the Real Estate Industry Contributes to Racial Disparities in the U.S. and How It Can Do Better

SoWha?!?

RiNo and LoHi and LoDo… SloHi! Surely you’ve noticed the proliferation of cute neighborhood names taking over Denver. Even South Park joined in on the action by renaming Kenny’s neighborhood, SoDoSoPa. Many view these new names as a signal of a neighborhood “arriving.” On closer inspection, it is part of the “re-branding” of neighborhoods that were once considered unsafe for white folks. It is an early step in gentrification.

- LoHi, SloHi, or anything Highland was once known as Northwest Denver to the Latino community who resided there previously.

- LoDo (Lower Downtown) was known as a skid row until Denver City Council established the Lower Downtown Historic District in 1988.

- RiNo (sometimes known as River North) wasn’t established until about 15 years ago, when it was mostly warehouses and light industrial buildings on the edge of Five Points. Five Points is Denver’s most notable historic African-American neighborhood.

What is Gentrification?

Gentrification is the process of changing historically impoverished neighborhoods into areas that better conform to middle class tastes; re-branding is an early step in this process. (These historically impoverished neighborhoods are oftentimes occupied by minorities- for reasons that we will explore in this deep dive into the ways that real estate fits into the Black Lives Matter movement.)

While gentrification has become a buzzword, the concept is still misunderstood. It is important to look at gentrification within the larger historical context of real estate practices that are discriminatory toward minorities, especially black and brown people.

What is redlining in real estate?

“Redlining destroyed the possibility of investment wherever black people lived.”

—Ta-Nehisi Coates

An original map of Denver with redlined areas.

The US government established redlining in the 1930s. In this practice, government surveyors color coded different areas of the map as green (best), blue (still desirable), yellow (declining), and red (hazardous). The federal government deemed the redlined areas as credit risks and they based this determination on, primarily, racial composition of the neighborhood. The federal government would not back mortgages for homes in the red areas of the map.

As real estate professionals, we know that the federal government’s backing of mortgages in the United States is why there is a middle class. Folks who don’t work in this field day in and day out may not be aware of the impact of this government action. Want an example of a federally-backed loan? How about VA loans, loans specifically for veterans. Because of redlining, it was harder for black and brown veterans to buy homes and build wealth than it was for white veterans who were able to more widely use the loans made available to them by the VA home loan program, created in 1944. This is just one example. The majority of home loans in the United States are either federally-backed or structured according to federal standards .

The practice of redlining had several immediate consequences and the ongoing impacts are traceable to the current day. In short, people of color faced significant barriers in obtaining loans. Furthermore, homes they owned in redlined areas would have significantly depressed values.

The way that Americans build wealth is through home ownership. It is, after all, the American Dream. However, through redlining, people of color have been systemically denied this opportunity.

Today, more than 30% of first time home buyers make their down payment using a gift from their parents or other family members. If those parents and their parents and grandparents did not have the opportunity to build wealth through home ownership, then are they in the position to gift a down payment to their kids and grand kids? Probably not. Not to mention that people use the wealth generated by home ownership for lots of other things that help them pursue their dreams, go to college, start a business, and more.

Redlining and its ripples are multilayered and complex and beyond the scope of this post. However, if you would like to learn more about redlining, check out these deep dive resources:

- The history of redlining

- The racist policy that made your neighborhood

- America’s formally redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to protect them

- Redlining was banned 50 years ago. It’s still hurting minorities today.

But Wait There’s More… forms of Housing Discrimination

Redlining wasn’t the only practice in place that precluded people of color from their pursuits of wealth and happiness. For example, until 1956, the Realtor code of ethics actually required racial discrimination. The code read:

962 newspaper ad for the Saturday Evening Post

“A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.”

In other words, Realtors shouldn’t sell homes in white neighborhoods to black and brown home buyers. To be completely clear, the National Association of Realtors is a professional lobbying organization. Many people use the words Realtor and “real estate agent” interchangeably, but they are not the same thing. It’s like squares and rectangles. All Realtors are real estate agents but not all real estate agents are Realtors.

Neighborhood covenants have also been used to exclude minorities and people of color from purchasing homes in certain areas. Once the Supreme Court determined that states could no longer enforce such racist covenants, the real estate industry then turned to a strategy known as blockbusting. Real estate agents stoked the fears that the racial integration of a neighborhood would dramatically decrease property values, getting white homeowners to sell their homes at a loss. As white flight increased, home values in these neighborhoods dropped, further limiting the equity gains experienced by black and brown homeowners.

The Fair Housing Act Falls Short

‘If you sought to advantage one group of Americans and disadvantage another, you could scarcely choose a more graceful method than housing discrimination.”

—Ta-Nehisi Coates

During the riots that ensued after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. This act was meant as a follow-up to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and included the Fair Housing Act. The Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination in the sale or rental of property on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin (adding disability and family status in 1988).

Despite the intentions of the Fair Housing Act, it didn’t alleviate the high levels of segregation experienced throughout the United States. The Act places the burden of enforcement on victims, requiring them to file their complaint with the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) or sue in federal court. As a result, high levels of housing segregation persisted in urban neighborhoods.

Yard signs opposing high rise development in a Highland neighborhood.

In the years following the Fair Housing Act, white communities have successfully blocked undesirable development, such as affordable housing, homeless shelters, freeways, and polluting industries. This brand of NIMBYism (an acronym meaning Not in My Back Yard) places a disproportionate burden of those developments on communities of color. The disproportionate negative impact on the built environment creates greater health risks within the community. Many of these communities also suffered a lack of municipal investment in neighborhood infrastructure, such as parks, schools, playgrounds, and safety measures like sidewalks.

Even though the Fair Housing Act banned racial discrimination in lending, a 2017 study conducted by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting showed that banks and other lenders denied African Americans and Latinos conventional loans at a much higher rate than white borrowers. The study showed that modern day redlining persists in 61 metro areas even when considering applicants’ income, loan amount and neighborhoods are similar.

Starting in the 1970s, the home ownership gap between whites and African Americans started to shrink. However, we have backtracked on this progress since the housing bust of 2008 that resulted in disproportionate denials and minimal anti-discrimination enforcement.

The home ownership gap between whites and African Americans is currently wider than it was during the Jim Crow era.

More Discriminatory Practices By Real Estate Agents

In the real estate industry, implicit biases often affect the home buying experience for black and brown home buyers.

In the real estate industry, implicit biases often affect the home buying experience for black and brown home buyers.  While not intentionally attempting to be racists, many agents have been found to steer clients to segregated neighborhoods based on assumptions about their needs based on race and class. A three year study conducted by Newsday and published in 2019 showed that 19% of Asians, 39% of Hispanics and 49% of blacks experienced unequal treatment by real estate agents in Long Island.

While not intentionally attempting to be racists, many agents have been found to steer clients to segregated neighborhoods based on assumptions about their needs based on race and class. A three year study conducted by Newsday and published in 2019 showed that 19% of Asians, 39% of Hispanics and 49% of blacks experienced unequal treatment by real estate agents in Long Island.

Such actions included:

- Warning white home buyers about gang-violence in black neighborhoods, but not disclosing the same facts to a black home buyer

- Identifying specific minority neighborhoods as prime for “buying crack”

- Omitting listings in white neighborhoods for interested black home buyers

- Advising white home buyers to observe moms waiting at a school bus stop and buying diapers at the grocery store (to identify the racial composition of neighborhood mothers)

- Placing black and Hispanic home buyers under additional financial scrutiny like requiring pre-approval and a signed agency agreement before showing listings

This study shows conclusively that the real estate industry still practices acts of housing discrimination despite Fair Housing Act rules. The practices have just become more subtle.

Gentrification Comes for Minority Communities

In 2019, there were well over 200 instances in the Denver Metrolist MLS where a real estate agent used words in a listing description signaling the home was located in a gentrifying neighborhood, including “up and coming,” “changing,” and “improving.” A few agents even used the word “gentrification” in their listing descriptions in the last year. These euphemisms signal the neighborhood is more worthwhile than in years past. Furthermore, the bargain of purchasing now will pay off in the future as demand increases while the demographics change.

The promise of gentrification presents an opportunity for white middle class home buyers to invest in a neighborhood that has experienced many years of systemic financial neglect and it’s citizens’ having experienced generations of discrimination and segregation in housing. These home buyers are able to buy low and then see massive returns. Gentrifying neighborhoods typically see a sudden explosion of hyper-investment as the neighborhood changes to suit the changing demographic.

The promise of gentrification presents an opportunity for white middle class home buyers to invest in a neighborhood that has experienced many years of systemic financial neglect and it’s citizens’ having experienced generations of discrimination and segregation in housing. These home buyers are able to buy low and then see massive returns. Gentrifying neighborhoods typically see a sudden explosion of hyper-investment as the neighborhood changes to suit the changing demographic.

a meme depicting gentrification

Gentrifiers Don’t Assimilate

As gentrification grows, property taxes increase and commercial rents rise. The neighborhood restaurant moves out to the suburbs, a coffee shop serving $6 pumpkin spice lattes moves in. Artisanal mayonnaise shops replace the corner barbershop. Food halls open up with promise of blending the needs of the diverse community. Yet, the only shops inside are specialty high-end butchers, hand-made pasta shops, artisanal bakeries, and craft breweries. An array of yoga, pilates, cross fit, and other fitness crazes meet the needs of the young, upwardly-mobile professional transplants.

White home buyers often like the idea of living in a diverse neighborhood. However, they rarely adapt to what the community offers and often insist on having the neighborhood adapt to their tastes.

The Criminalization of Gentrifying Neighborhoods

A white woman calls the police on a black family having a bbq, becomes an internet meme instead

The unwillingness of gentrifiers to adapt becomes problematic when it comes to the issue of policing. We don’t need to rehash current events, but the availability of video footage of numerous, horrible and shocking crimes against black people by police officers has shed light on the fact that police officers are 2.5 times more likely to kill black people than white people.

There are also numerous videos on social media showing white people calling the cops on black people doing everyday, non-threatening activities such as bird-watching or having a bbq with family in a park. The influx of higher income residents within gentrifying communities  often creates increased expectations for safety and public order. New bars, pubs and breweries in these neighborhoods demand increased police presence. Additionally, new residents alert the police to nuisances at a higher rate than previous residents did. In 2013, San Francisco launched Open311, an app that allows residents to report loitering, dirty sidewalks, and vandalism by just snapping a photo. After the app launched, gentrifying neighborhoods saw a disproportionate spike in police activity.

often creates increased expectations for safety and public order. New bars, pubs and breweries in these neighborhoods demand increased police presence. Additionally, new residents alert the police to nuisances at a higher rate than previous residents did. In 2013, San Francisco launched Open311, an app that allows residents to report loitering, dirty sidewalks, and vandalism by just snapping a photo. After the app launched, gentrifying neighborhoods saw a disproportionate spike in police activity.

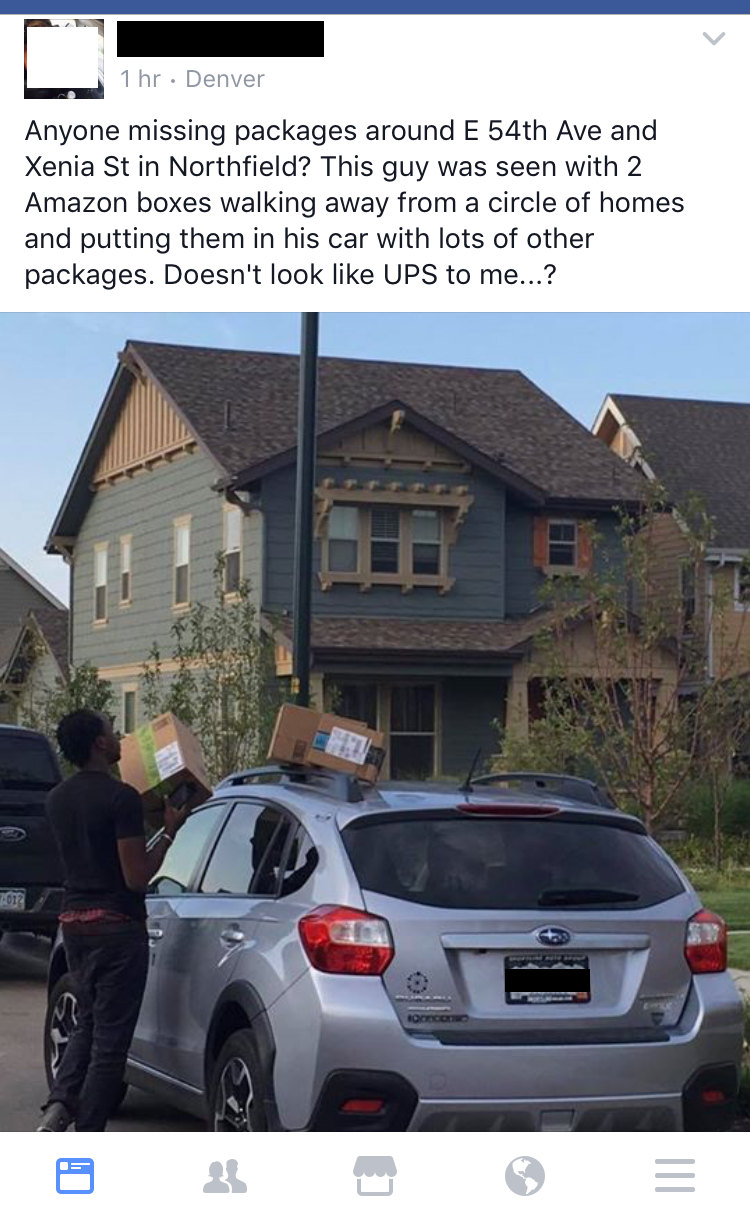

Social media, such as Nextdoor and Facebook groups have made it easy for neighbors to profile “suspicious activity.” While violent crime is at its lowest rate in decades, public perception is that crime is far worse due to the amplification of incidents on these hyperlocal platforms. Nextdoor has taken steps to curtail racial profiling on its site, it is still difficult to fix perceptions of users and to prevent discriminatory practices when using the site. Fear and suspicion are still crippling problems when it comes to black/white relations.

- Young men are reported for hanging out at a local park at night.

- A Hispanic man is harassed and reported for parking his car on a white woman’s street.

- A young man is accused of stealing packages. It is later revealed that he was delivering packages for Amazon.

Why does it matter that gentrifying neighborhoods have increased police presence? Increased police presence amplifies the risk of police misconduct and violence. A prime example occurred in San Francisco’s Bernal Heights neighborhood when police killed Alex Nieto. A white couple who recently moved into the neighborhood called the police on Nieto when they witnessed his brief altercation with an acquaintance of his. They reported a man with a handgun wearing a red jacket (a San Francisco 49ers jacket), and further insinuated that the jacket’s color was associated with gang activity. When the police arrived, they mistook Nieto’s taser for a handgun. In response, they shot at him 59 times, killing him.

A mural and tribute to George Floyd outside of Cub Foods in Minneapolis. Painted by Xena Goldman, Greta McLain, and Cadex Herrera.

Incidents like this have resurfaced all over the United States. The availability of video coverage has many of us questioning the use of force by police. While police reform is essential, we all need to consider how our own actions affect those in the black community.

The Financial Impact of Housing Discrimination

The cumulative effects of redlining, gentrification, and the continuation of unfair and biased real estate and lending practices have kept home values low for minority homeowners and have prevented minorities from owning at the same rate as their white counterparts. With depressed home values and less access to home ownership, black and brown families struggle to accumulate generational wealth. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the median net worth for an African American family is $9,000 and is $12,000 for a Latino family. In comparison, the median net worth of a white family is $132,000. As noted earlier, wealth from home equity helps white families pass on wealth across generations. Without generational wealth and with depressed home values and little access to home ownership, these communities are vulnerable to gentrification.

Where Do We Go From Here and What Can We Do?

As an industry, it is easy for real estate agents to say that they support Black Lives Matter, that they support their black colleagues, and they treat everyone equally. It is easy to say you are against gentrification. However, it is another thing for us to actually implement action. Conversations regarding gentrification always focus on avoidance of the subject and minimizing agent liability. The real estate industry should consider how we market and whether our practices are fair for all potential home buyers.

During this most recent housing boom, agents began encouraging clients to write “love letters” to home sellers as extra consideration to their offers when the home buying process was competitive (at Bluebird Real Estate, we did this too). The practice was problematic as buyers started including pictures of themselves and their families, revealing race and family status. Some of these aspects could potentially sway homeowners’ decisions when choosing between two or more similar offers. Bluebird Real Estate began discouraging homeowners from reviewing these letters in 2017. In 2019, the Real Estate Board followed suit.

What can real estate agents do to improve their service to communities of color? We can start by educating ourselves, looking inward to understand how our actions result in the disenfranchisement of minority communities.

What can real estate agents do to improve their service to communities of color? We can start by educating ourselves, looking inward to understand how our actions result in the disenfranchisement of minority communities.

We should work to stop NIMBYism as it limits the supply of homes and burdens black and brown communities. Increasing urban density in less dense urban communities is necessary. Affordable housing should be built throughout the city, not just in minority neighborhoods. We should all work to become YIMBYs.

Many activists have called for more required education for police officers. Perhaps a stronger educational requirement to enter the real estate field is also necessary. Agents need more education that focuses on how issues like redlining and blockbusting have lead to racial disparities. 100% of real estate agents should know that gentrification is a problem, not a positive development.

Most importantly, we should all consider our own biases. It is easy to be critical of the actions of others. Yet, the easiest changes come from within. Question your assumptions. Understand your privilege. Step out of your comfort zone. Admit when you’re wrong. Be an ally. Hold others accountable. Listen. Support. Don’t be silent. End white supremacy. We will do our part. We hope you can do the same. Thank you for reading.

**If you’d like to keep this conversation going, you can opt in to our Anti-Racism in Real Estate discussion group. (By opting in you are not signing up for any other marketing or solicitation lists.)**